Abby and her children at their camp in Yellowstone c. 1905

Well depending on your criteria, "the first" could be argued, but in that first handful. ;-) Abby Williams Hill was definitely leading the way for women out West. A very impressive artist and mother who pursued a life that defied conventions!

Abby Williams Hill (1861-1943) was a landscape painter, social activist, prolific writer and mother of four, with a great love of travel and learning. She produced a remarkable collection of landscape paintings showcasing the grandeur of the American West, as well as a vast archive of letters and journals addressing issues of continuing social and historical interest including education, tourism, the environment, and the rights of women, Native Americans, African Americans, and the working class.

She did follow the convention of 'married with children', but that's about where it stopped. Preferring a life in the wilderness, traveling and painting, rather than a life of domesticity and social obligations. This adventurous painter completed most of her canvases outside on location. While usually bringing her children into the wilderness - along with home schooling supplies, camping and painting gear - as her doctor/husband remained at home.

Not only was she a front runner for female artists painting the American western landscape, she was also spearheading social and progressive causes too. Abby established a Washington State chapter for the Congress of Mothers - later to be called the National Parent-Teacher Association - and was the first state president.

This photo I took at the University of Puget Sound where the painting is displayed ...

Yellowstone Falls (from below) by Abby Williams Hill Oil c. 1905

If you’ve followed my blog for a while, you may recognize Abby Williams Hill from my Mother’s Day post in 2017, where I introduced you briefly to her and her work. Today, the majority of Abby Williams Hill's art and writing is in the collection of the University of Puget Sound in Tacoma, WA. Many years ago, I visited and toured with the curator to see her art, journals and papers in person.

I consider her a ‘kindred spirit’. :-) So I'd love to go much more in depth on her life and work. Here, in my female artist series for Women's History Month, she deserves a deeper dive!

Born Abby Rhoda Williams in 1861 into one of the founding families of Grinnell Iowa. Her parents were Henry Williams and Harriett Porter. She was their second daughter, having a sister Nettie (sometimes called Jeanette) who was born two years before her in 1859. Both girls grew up and received their education in Grinnell. An aunt who was a botanical watercolorist, provided early art inspiration for Abby.

Choosing to pursue a painting career, in 1880 Abby moved to Chicago to study with H.F. Spread, a founder of the Chicago Academy of Art. While there, she stayed with the family of a German minister and traded her knowledge of music, teaching their children, in exchange for German language lessons.

After her time in Chicago, she returned to Grinnell and began teaching. Shortly thereafter, she accepted a position in Quebec at a girl’s seminary where she taught painting and drawing. The position also offered an opportunity to study French.

While teaching, she was also painting the local landscapes and even painted as far away as the eastern seashore. In the summers, she exhibited these works in Iowa, receiving accolades in the Grinnell press.

Roses by Abby Williams Hill Oil c. 1906

In 1888, she chose to leave her teaching job in Quebec and continue her painting studies. She went to New York to study with William Merritt Chase at the Art Students League. Chase was considered one of the most innovative and influential teachers of the time.

While Abby was his student there, he stated “… Miss Williams, you can go to the top if you want to. You have talent and you have a genus for work; they go together.”

Later Abby quoted Chase as having told her…”artists make the world more beautiful for others because they see more of its beauties and so teach others to see them.”

In New York, she met (or possibly was reacquainted with) a fellow Grinnellian, Dr. Frank Hill. They were married in December 1888.

In those New York newspapers, there was lure of the magnificent Pacific Northwest and the area of Tacoma was mentioned, touting the wild and picturesque landscape. This may have been what prompted the couple's move to Tacoma Washington in 1889 - the same year the Washington Territory became the forty second state.

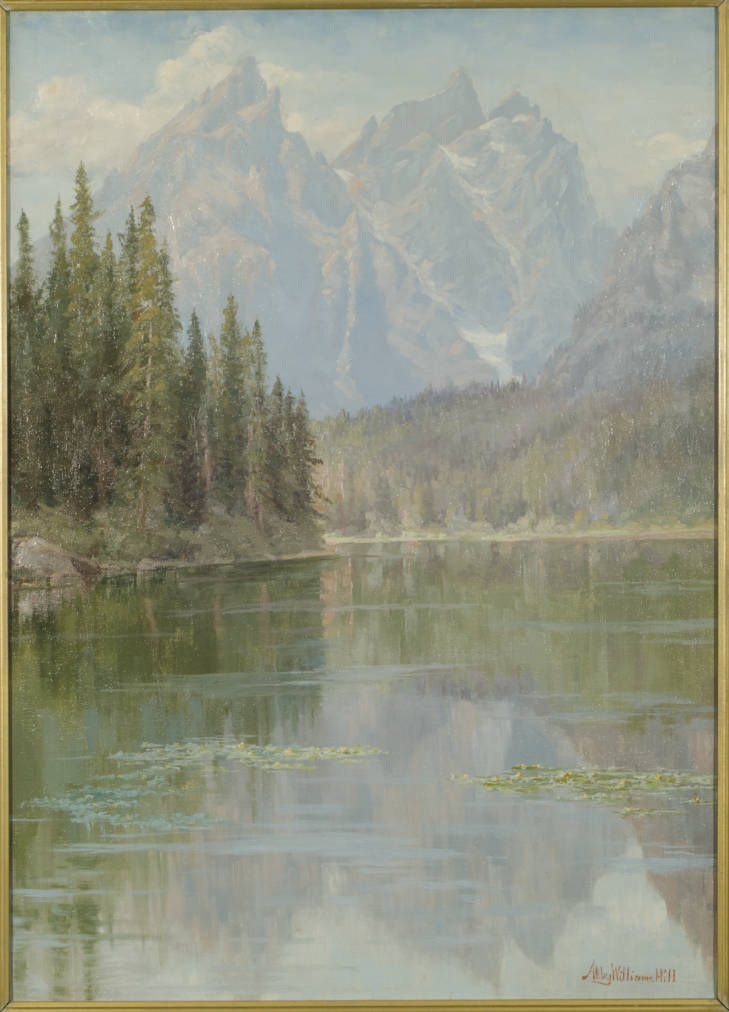

String Lake (Wyoming) by Abby Williams Hill Oil c. 1931

A very full year for Abby!...since also in 1889 in Washington, Abby gave birth to her only biological child, a son Romayne Bradford Hill (1889-1978), who was born partially paralyzed on his left side. He needed almost constant care until he could turn over himself at 2 years old and learned to walk at 3. Abby had little time for her own art work during this period as she had customary social obligations as a doctor’s wife as well. Only a few smaller works remain from these years.

Most likely a large reason for moving to the area was for her painting, however she wasn’t able to take full advantage of the incredible scenery of the Pacific Northwest for several more years...

Then, in 1894, Abby spent weekends and summers on nearby Vashon Island. Her son's health seemed to be improving or at least they were managing it better. This time period re-ignited her interest in hiking, camping, and painting en plein air.

In the summer of 1895, she had her first experience of painting in the ‘wilds’ of the American West. She joined an expedition into the Cascade Mountains, learning first hand some of the wilderness skills that would be valuable throughout her later adventures. Although, many members of the group were set on scaling Mount Rainier, she took along her paints, brushes and easel and set up to paint in spots along the way.

A journal from this period describes some of her early wilderness experiences… The tent collapsed twice during the first night, her knee-length skirt and leggings took some "getting used to" and more experienced hikers had to outfit her shoes with cork for comfort and hobnails for safety.

"I sketched all the afternoon, sitting on a precipice just about a foot wide, and perhaps three hundred down. Two men warned me and declared that they would not dare sit there. Women are supposed to be more clinging than men.” (Abby Hill's diary, as quoted by Ronald Fields, Abby Williams Hill and the Lure of the West, p. 17)

Mt. Rainier From Vashon Island by Abby Williams Hill Oil c. 1900

Almost immediately after her return from the Mount Rainier excursion, she embarked on a similar excursion to the Hood Canal at the foot of the Olympic Mountains. Yet another difficult hike presented itself, as the group made its way through virgin forests and across numerous waterways.

"After the pools, came the wildest scenery and the most severe climbing, up rocky sides, over boulders and under them, across streams on logs many feet above the whistling torrent, and at last seated to sketch in a place where the roar was so great, I could not make my companion on the next rock hear my voice...

It was thought no woman had ventured as far as I did today" (Fields, p. 18).

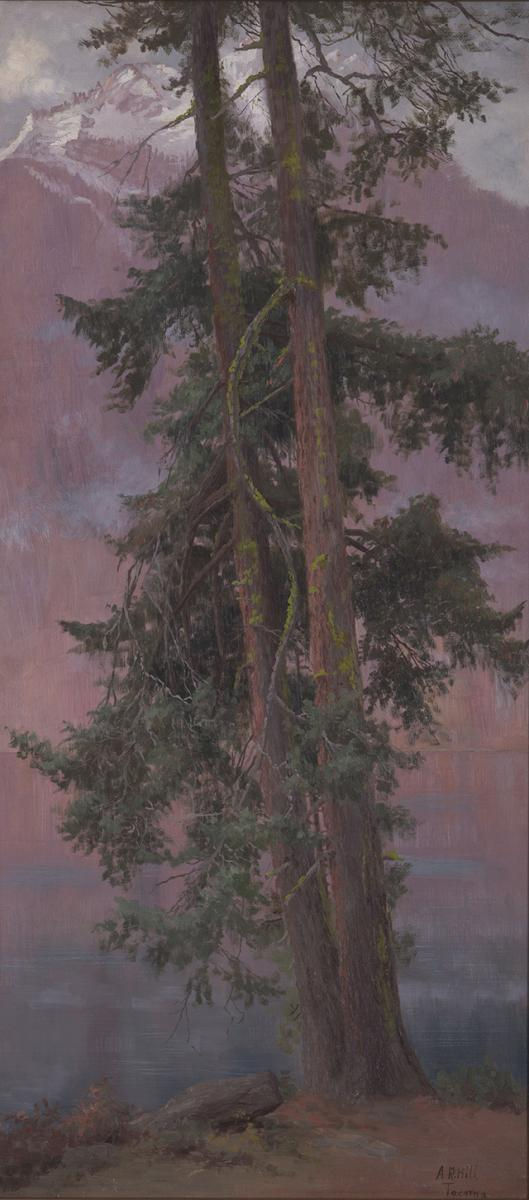

Fir Trees Lake Chelan by Abby Williams Hill Oil c. 1903

Two days after her return, the family left Tacoma, and headed East. Their plan was for Frank to go to a medical conference in Minneapolis, their son could see a medical specialist, they would visit family and eventually leave for a two year stay in Europe to further Frank's study of medicine... and then would return to Tacoma.

They were in Hamburg, Germany for 6 months, where Abby took the opportunity to study with illustrator Hermann Haase, while her husband continued his study of medicine. The rest of the time they seemed to be mostly traveling throughout Europe.

When they returned from Europe to Tacoma, they had made the decision to adopt... Eulalie (1891-1978) was adopted in 1898. Frank, on board for this first adoption, was not so sure about further adoptions because of the cost and health concerns they had already in the family. But Abby had received an inheritance (today it would be more than a half million dollars), so she undertook the financial responsibility of the other adoptions. Ione (1886-1984) was adopted in 1899, and Ina (1889-1987), Eulalia’s older sister, came into the family in 1901 - although Ina was not officially adopted until years later.

At this time, Abby decided she would home-school her children.

She was spending time on Vashon Island, not far from Tacoma, with the children while making Art. Around 1899 they began extended camping trips on the Island. Generally, Frank remained in Tacoma. From July to mid-September the Vashon Island camp became home to her and the children...

“We must have town clothes, and we must have a botany outfit and we must have a bag of books and we must have a sketching outfit and we must have articles for preserving specimens and we must have an outfit for insects and - - and by the time these musts were piled on the beach and added to them, tents, bags, provisions, no one could have disputed the party’s right to the name of Hill.”

To Abby, it was an ideal situation for her and the children... She could be outdoors painting again and they could adventure and learn. Since she had such a strong disdain for fashion and ‘dressing’ - particularly proper female attire of the day - camping was more to her liking! So she was happy away from society pressures and social obligations.

In the Spring of 1903, she received a commission from the Great Northern Railway. The first woman to work on contract for them. Part of the offer would involve free rail passes for herself and her children - a very good incentive for a woman so interested in traveling. The Officers of the Great Northern Railway wanted her to travel and paint the area around Lake Chelan, Washington. A fifty mile long lake in the North Cascades. It was considered some of the most rugged and inaccessible scenery of the Cascades which she would have to negotiate without the benefit of established, managed camps.

Looking Down Lake Chelan by Abby Williams Hill Oil c. 1903

She produced about twenty canvases there with her children, before autumn weather made the area impassable.

Discussing her work at Chelan Gorge, Abby reported that ...

"It has been the most difficult sketch I ever made owing to the heat and its being so out of the way...." (Fields, p. 37).

Then an autumn snow storm surprised the artist and her children. Living in a tent with no heat, they were obliged to endure the cold and live off raw foods for two days. This was not the only mention of 'camping incidents'... At her various campsites, she usually kept a journal, describing encounters with snakes, landslides, Indians on horseback, rain, wind and bears in Yellowstone. Many adventures were had!

"Cliffs at Eunice Lake" is the front cover of my book of Abby Williams Hill by Ronald Fields.

Abby and her children survived these trials, and her paintings from the North Cascades succeeded wonderfully, earning her enviable praise when they were first shown in Tacoma. Her renown even made its way to distant Grinnell, where on December 29, 1903 the Grinnell Herald reprinted from the Tacoma Daily News a most favorable review of Hill's canvases, "soon to shine at the St. Louis exhibition".

The Railroad published 30,000 copies of a pamphlet highlighting these 20 paintings of the North Cascades. And, all 20 paintings were displayed at the 1904 Worlds Fair in St. Louis. Her contract with the Railroad entitled her to have all these paintings returned to her at the end of the World's Fair. A very smart ‘business move’, which meant she would retain all of those commissioned pieces herself - keeping quite a personal collection intact!

Her fame also made its way to the headquarters of the Northern Pacific Railway, which in 1904 issued her the first of three new painting contracts. The first called on Abby to travel to and paint Mt. Rainier and the Monte Cristo Mountains, along with sites in Idaho and Montana. The eleven canvases that resulted from this commission were exhibited at the 1905 Lewis and Clark Exposition in Portland.

Emerald Pool by Abby Williams Hill c. 1906 in Yellowstone

Abby's work in 1904 evidently pleased officials of the Northern Pacific, who in the spring of 1905 extended her yet another commission, this one taking her to Yellowstone Park where, in the course of about a month, she produced three paintings—two of Yellowstone Falls and one of the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone. As with her earlier expeditions, Hill found the going tough:

"The view I selected [to paint] was from a cliff extending over the canyon. It is not over three feet wide and [has] a very sharp descent to reach it. I thought to pitch my little tent on it, but after sitting there till noon, there came up such a wind we crawled off between gusts and concluded a tent with a floor in it would fill and carry us with it" (Fields, p. 66)

Abby's children in the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone with one of her canvases.

When painting Yellowstone Falls, calamity very nearly did strike:

"Got out on my perch and painted a few hours...when suddenly there came a roar and without more warning, a big twister struck us, wrenching the picture from its fastening, jerking it under the poles and away down the canyon, which is at least 400 feet deep and the sides almost perpendicular..." (Fields, p. 67)

The next day volunteers descended by rope more than 100 feet along the canyon walls, and retrieved the canvas. She brushed it off and continued painting.

Yellowstone Falls (distant view) by Abby Williams Hill Oil c. 1905

Abby's third and final commission from the Northern Pacific took her back to Yellowstone in 1906. The details of the contract remain unknown, but we know that before reaching the park, she visited both Minneapolis where she took part in a meeting of the Congress of Mothers (later the National Parent Teacher Association), and then on to Grinnell, where in April her father had died. Besides settling details of her father's estate, Abby also worked out the details of the trip to Yellowstone while in Grinnell, writing her husband to make arrangements for the entire family to meet in Montana.

Firehole Pool by Abby Williams Hill

(looks a lot like Cliff Geyser in Black Sand Basin which I have painted!)

The subject matter of the last railroad commission evidently centered on Yellowstone's geysers, but Abby preceded her visit to the Park with a stop at the Flathead Reservation, a reminder of her interest in and defense of Native American causes that she pursued more vigorously later in her career.

In Yellowstone, bears and other animals were abundant. Thinking the bears relatively harmless, Abby often fed and photographed those that appeared at camp during daylight. Tourists she regarded as more harmful, and she did what she could to avoid them.

Ronald Fields deduced from Abby's journals that she completed fifteen paintings that summer in Yellowstone, but only a few are known to the Puget Sound collection and none has a connection with Grinnell.

After leaving the Park, Abby remained for a time in Montana, again visiting with and painting at the Flathead Reservation where she observed regretfully the incursion of destructive outside influences. The paintings of Native Americans represented a new direction in her work, increasingly devoted to individual portraits and to documenting native American cultures. As a result, she developed strong bonds among the Salish (known to some as Flatheads), the Nez Perce, the Yakama, and others. Her paintings provided a unique and sympathetic introduction into their lives.

Empty Papoose Case by Abby Williams Hill Oil c. 1906

By the end of 1906, Abby had completed four intensive years of commissioned work for the railway companies and produced for them more than 55 documented landscape canvases. Now, she was being offered more commissions from other railway companies. She turned them down to take her children on a long-awaited European trip.

Abby and the children left Tacoma with loose plans to eventually sail to Europe, first stopping in Montana for some 'wilderness time', camping for 6 weeks on Lake McDonald and then stopping in Harlem, Montana to create more Native American pieces. She also stopped to visit family further east, fulfill some of her obligations for the Congress of Mothers, and also again see specialists for her son's medical condition.

Belgium sketch by Abby Williams Hill c. 1908

All the while, her letters back to her husband in Tacoma spoke of concerns of the current financial crisis. Her concerns caused her to delay their European departure until March 1908, to be sure they would not get stranded in Europe without funds. Her letters also continually requested for Frank to join them, but he spoke of excessive work and the need to attend to financial matters. He had invested heavily in irrigation and crop projects in eastern Washington unsuccessfully.

In the fall of 1909, Dr. Frank Hill suffered a "mental breakdown". From their previous letters, Abby seemed to not know the complete extent of Frank's condition. She was notified to return as quickly as possible to Tacoma. There, she found him suffering from "extreme melancholia" and "frequent lapses into a catatonic state for weeks at a time." A Seattle physician suggested taking him to a sunny climate, so Abby sent the children off to college and took Frank to southern California.

For years, she struggled to care for him. Giving up much of her painting career and independence to help him recover. From 1913 - 1921, she lived in an isolated beach house in Laguna Beach, California painting only limited beach scenes and nearby Niquel Canyon.

Laguna Beach Scene, 1912

In 1921, Frank was admitted to Patton State Hospital in Patton, California. At that time, Abby spent two months with Romayne and Ina in Yosemite. But Frank remained in the hospital until 1924, so Abby also remained in California during that time.

When he was released in 1924, Abby bought a large automobile and with herself, Frank, Romayne and Ina began their "gypsy phase". They set off traveling... Two years were spent in Alabama, Mississippi and Arkansas.

Cliffs, Emerald Bay Laguna Beach California by Abby WIlliams Hill Oil c. 1915

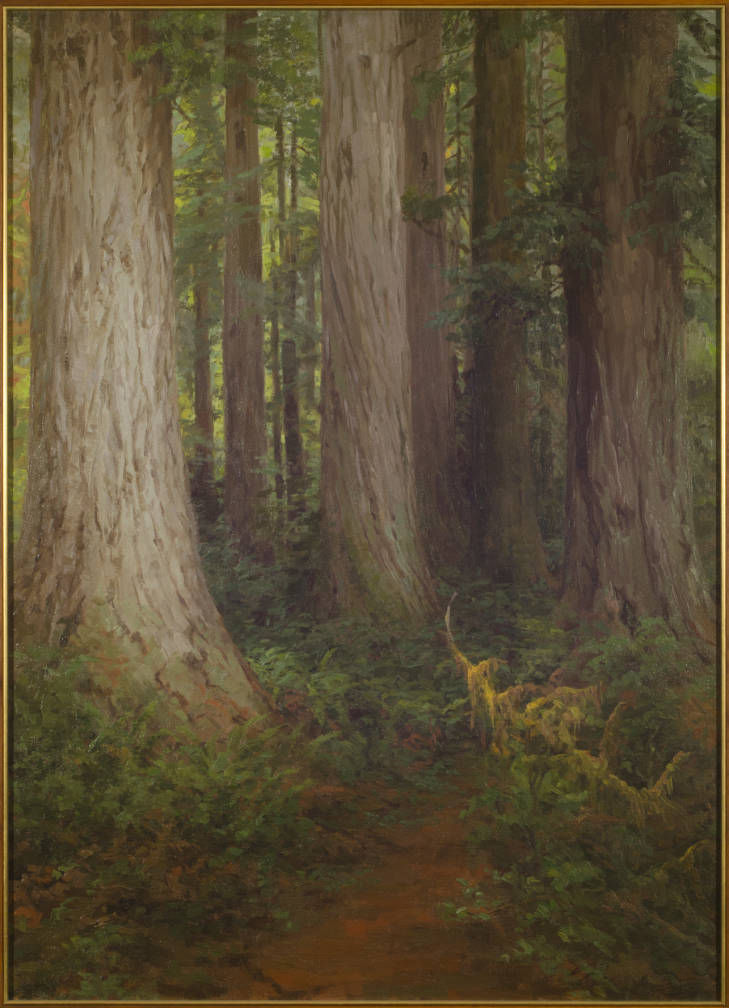

Then they all headed back West. She was concerned with the threat that commercial and tourist interests posed to the natural environment. She noted that several of the landscapes that she had painted earlier in her career no longer existed in the state in which she had observed them. In response, she embarked on a series of paintings of western National Parks, which she considered her legacy to future generations.

They camped from spring to autumn at various Parks in the West and spent winters camped in Tucson Arizona. During winters in Arizona, Frank could use his medical expertise to help with tuberculosis patients. All seemed to be going well, until Frank's illness appeared in 1931. He returned to Patton State Hospital and Abby moved back to California.

Redwoods by Abby Williams Hill Oil c. 1934

Frank never left the Patton State Hospital this time. Following the death of her husband in 1938, Abby became "bedridden" - speculating complete physical and mental exhaustion - and eventually died in 1943 in Laguna Beach, California.

After Abby's death, Ina Hill presented the University of Puget Sound the majority of her artwork and journals. Compared to many artists, the collection of her work is relatively intact here, since she retained possession of most of her painting commissions. Ronald Fields, an art professor at the University, eventually researched and wrote Abby Williams Hill and the Lure of the West... a very good place to start if you'd like to know more about her.

Flathead Indian Reservation Looking East From Ronan Montana

by Abby Williams Hill

Oil c. 1905

As we culminate Women's History Month in March, this culminates my weekly essays featuring historic women artists. I hope the series provided some value to you. I'm opened to ideas for future posts. So if you have comments or ideas, I'd love to hear from you... contact me anytime; shirl@shirlireland.com

Thanks for reading. I hope you've learned some interesting Art History during Women's History Month!

P.S. - And now our 'deeper dive' if you'd like to go there...

It's fun to dig into the idea of the "first" female plein air artists painting the landscape around the Western United States, which I call home today. It really hasn't been all that long that women were "granted the privileges" to study Art and go about painting the subjects they preferred where and when they wanted.... even if those subjects were outside the home! Hard to imagine now, as I plein air paint 'unchaperoned' whenever I want, but it was a very progressive idea of the time.

Below are some other very early prominent female artists of Western landscapes or "open-air" painting. They were all quite early to the game, therefore carry very intriguing stories! A great place to 'dig a little deeper' if you'd like...

Constance Gordon-Cumming (1837-1924) from Scotland who traveled world wide to paint the landscape in Australia, New Zealand, Americas, China and Japan. She painted Yosemite in the 1880's, mostly watercolors, and exhibited her work in the first 'Yosemite Art Show'.

Louise-Joséphine Sarazin del Belmont (1790-1871) a very early European female plein air artist, mostly working in France and Italy. Historians question how, as a woman, she was able to move around and paint seemingly so freely in her era, when those freedoms were really not given to women quite yet.

Eliza Greatorex (1819-1897) created the book Summer Etchings in Colorado (1873). She lived in NYC and received a commission to produce those etchings of Colorado. Earlier in her career she did paint, but a health issue sent her into more pen and ink drawings.

Paina Wurti, or "painter woman" to the Hopis - Kate Thomson Cory (1861-1958) was an artist who spent a significant amount of time living, photographing and painting the Hopis in Arizona around 1905-1911.

Fidelia Bridges (1834-1932) was one of the few early female artists to pursue nature subjects almost exclusively, as the larger world of art began opening up to women.

Fidelia Bridges outfitted for painting in the field in 1864.

Comments